Pre-twentieth century

The Ishango bone

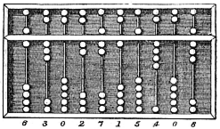

The Chinese Suanpan (算盘) (the number represented on this abacus is 6,302,715,408)

The ancient Greek-designed Antikythera mechanism, dating between 150 and 100 BC, is the world's oldest analog computer.

Many mechanical aids to calculation and measurement were constructed for astronomical and navigation use. The planisphere was a star chart invented by Abū Rayhān al-Bīrūnī in the early 11th century.[6] The astrolabe was invented in the Hellenistic world in either the 1st or 2nd centuries BC and is often attributed to Hipparchus. A combination of the planisphere and dioptra, the astrolabe was effectively an analog computer capable of working out several different kinds of problems in spherical astronomy. An astrolabe incorporating a mechanical calendar computer[7][8] and gear-wheels was invented by Abi Bakr of Isfahan, Persia in 1235.[9] Abū Rayhān al-Bīrūnī invented the first mechanical geared lunisolar calendar astrolabe,[10] an early fixed-wired knowledge processing machine[11] with a gear train and gear-wheels,[12] circa 1000 AD.

The sector, a calculating instrument used for solving problems in proportion, trigonometry, multiplication and division, and for various functions, such as squares and cube roots, was developed in the late 16th century and found application in gunnery, surveying and navigation.

The planimeter was a manual instrument to calculate the area of a closed figure by tracing over it with a mechanical linkage.

A slide rule

In the 1770s Pierre Jaquet-Droz, a Swiss watchmaker, built a mechanical doll (automata) that could write holding a quill pen. By switching the number and order of its internal wheels different letters, and hence different messages, could be produced. In effect, it could be mechanically "programmed" to read instructions. Along with two other complex machines, the doll is at the Musée d'Art et d'Histoire of Neuchâtel, Switzerland, and still operates.[13]

The tide-predicting machine invented by Sir William Thomson in 1872 was of great utility to navigation in shallow waters. It used a system of pulleys and wires to automatically calculate predicted tide levels for a set period at a particular location.

The differential analyser, a mechanical analog computer designed to solve differential equations by integration, used wheel-and-disc mechanisms to perform the integration. In 1876 Lord Kelvin had already discussed the possible construction of such calculators, but he had been stymied by the limited output torque of the ball-and-disk integrators.[14] In a differential analyzer, the output of one integrator drove the input of the next integrator, or a graphing output. The torque amplifier was the advance that allowed these machines to work. Starting in the 1920s, Vannevar Bush and others developed mechanical differential analyzers.

No comments:

Post a Comment